In the fight against food waste, a handful of states have enacted policies that ban some generators of food waste from sending food scraps to landfills. These laws are new, so data about their effectiveness isn’t widely available yet, but a pair of reports from Vermont and Massachusetts were released recently that show these policy solutions are making headway.

What Are Food Waste Bans?

Although the particulars of the policies differ, California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont have all passed food waste bans or mandatory recycling laws in recent years. Connecticut’s law, for instance, bans commercial entities that generate more than 104 tons of food waste per year from sending it to the landfill. That threshold goes down to 52 tons per year in 2020. Instead of sending food scraps to the trash, these businesses must donate food or recycle it through composting or anaerobic digestion, and hopefully put new policies in place that prevent or reduce food waste in the first place.

The end goal of food waste bans is to reduce the amount of food waste going to landfills, where it creates harmful greenhouse gasses, and instead divert good food to food-insecure citizens or use scraps to create valuable compost and energy.

Vermont and Massachusetts issued reports in December 2016 about their progress. Here’s how they are doing:

Massachusetts: Reducing Waste, Creating Jobs

Effective October 2014, Massachusetts made it illegal for businesses and institutions to dispose of more than 1 ton or more of “commercial organic material” in the trash per week. Instead they must donate it or send it for animal feed, composting or anaerobic digestion.

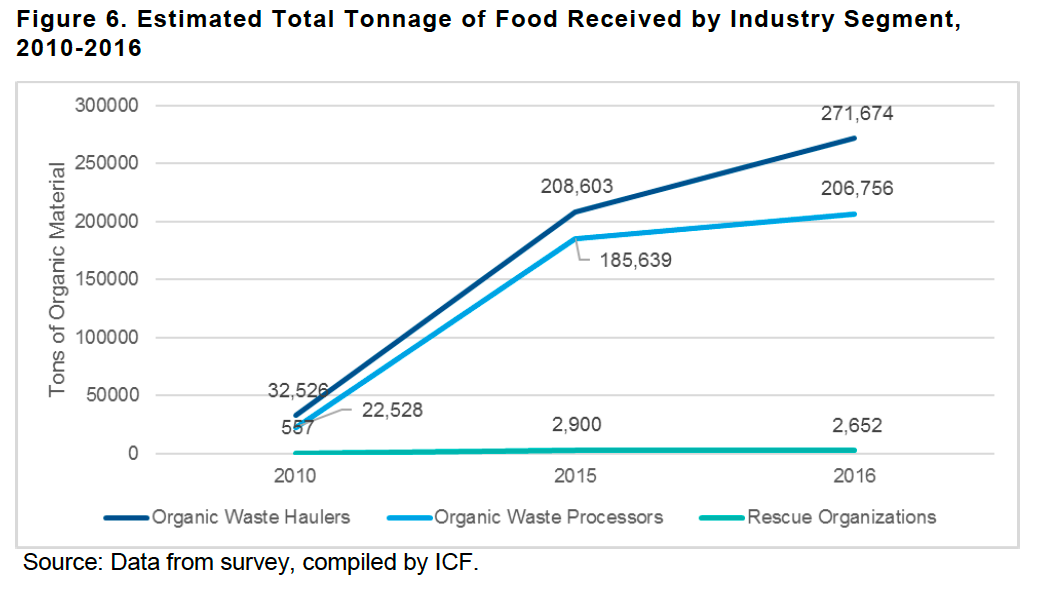

A survey of haulers, processors and food rescue organizations commissioned by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection found that the tonnage collected by the respondents has increased in 2016 to more than 270,000 tons from a baseline of 100,000 tons in 2010.

Massachusetts’s food waste ban has also generated $175 million in economic activity with $50.5 million in capital investments planned for 2017. The three groups surveyed all reported adding employees between 2010 and 2016 and projected additional job growth for 2017.

Vermont: Building a Market, Feeding People

Vermont’s Universal Recycling Law, which went into effect in 2014, bans individuals, businesses, municipalities and other entities from disposing a certain amount of food scraps per year. In 2016, that threshold was 26 tons; this year it goes down to 18 tons per year, which works out to one-third ton per week. Entities that are more than 20 miles from an organics processing facility are exempt until 2020. By 2020, food scraps will be completely banned from landfill.

A December, report from the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation found that overall trash disposal in the state decreased 5% from 2014 to 2015 and that recycling and composting increased by 2%. As a result of this law, all of Vermont’s towns and solid waste districts have adopted pay-as-you-throw pricing, meaning residents pay according to the amount of trash they produce, rather than a flat fee.

One of the greatest successes of Vermont’s law so far is the boost it’s giving to fresh food donation. The Vermont Food Bank reported a 25-30% increase in food donation in 2015 and another 40% increase in 2016. Much of that increase is in healthier, fresher foods rather than canned goods. This has brought food costs per meal for the Salvation Army of Greater Burlington Area to under $0.07 from $1.47 just two years ago.

One of the consequences of legislation like this is that it helps to assure potential investors in food donation and recycling infrastructure that there will be a ready supply of organic materials for new projects. Vermont now has 10 certified composting or anaerobic digesting facilities, 13 permitted food scrap haulers and 17 farm digesters to support the growing food waste reduction effort.

Challenges of Food Waste Bans

The news out of these New England states is encouraging, but challenges and barriers remain as the bans look to ramp up. In Vermont, the momentum must be maintained, and the public will need to be well educated about organics recycling before it becomes mandatory for all, if they want to meet their 47% diversion rate goal by 2022. The Massachusetts survey highlighted that space for composting facilities is limited, better source separation to prevent contamination is needed, and enforcement may need to be stricter. In Connecticut, anaerobic digester projects have been delayed due to delays in permitting and financing.

Overall, however, these early results are encouraging, especially if they inspire more states and municipalities to explore the feasibility of passing similar laws. Our country will need more states to try these solutions if we are to hit the EPA and USDA’s goal of reducing food waste by 50% by 2030 nationwide.